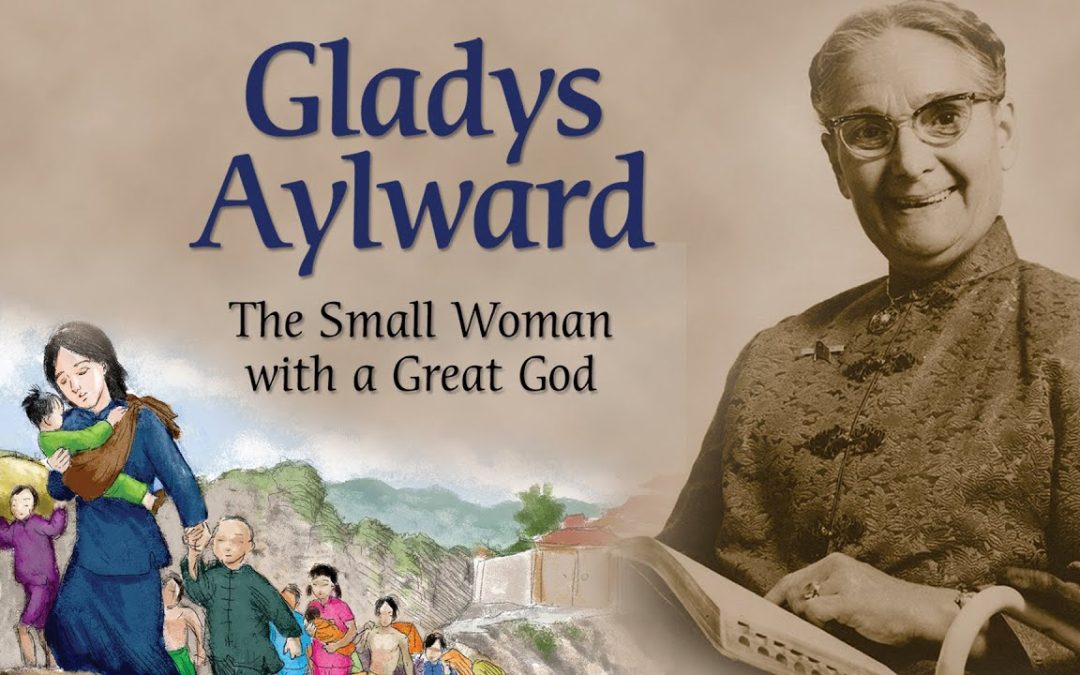

“I wasn’t God’s first choice in China. I don’t know who was, probably a well-educated man. If God has called you to China or any other place and you are sure in your own heart, let nothing deter you.” Gladys Aylward

1931 – Yangcheng, China: The regional governor stood at her door, “Miss Aylward, I need your help. I have come about your feet.” Gladys Aylward asked, “My feet?” The governor continued, “Yes, because you have big feet.” Puzzled,Gladys stared down at her tiny size three shoes. “You see, the government has decreed the ancient custom of binding girl’s feet illegal,” the governor explained. “You are the only woman in the region whose feet are not bound. I need you to be my foot inspector.”

“I am not interested in government politics, and I’m not interested in soles,” the 5-foot-tall British woman pushed back. “I am interested in souls for God.” The governor persisted, but the young missionary resisted. The next day the governor was back at her door. Eventually, Gladys agreed to become the foot inspector if she could tell villagers about her God. So it was that Gladys Aylward became the Minister of Feet in Yangcheng County not long after arriving in China.

Gladys grew up in a working-class family in the suburbs of London. She had little formal schooling before taking a job as a maid. After reading a China Inland Mission magazine article about the need for missionaries in China, she tried to recruit her brother to go. “If you really believe that someone ought to be going,” he responded, “why don’t you go yourself?” Gladys stood there motionless. It had never occurred to her that she should go. Was she the one? A few days later, a small voice confirmed that she was.

In 1929, 28-year-old Gladys was accepted to the China Inland Mission training program. Learning the Chinese language was difficult for her. After one year in the program, the director called her in. “We think you are too old to learn Chinese. We find you unfit for missionary service. You would be wasting our money and your life.” Gladys was heartbroken.

At church month later, she learned that 73-year-old Jeannie Lawson, a missionary in the mountains of northern China, was looking for a replacement. Lawson had been praying for a young person to replace her. Gladys sold all her clothes except the dress she wore and her favorite pair of shoes and bought a ticket on the Trans-Siberian Railway. The train took her across Europe, through Russia to Japan, where she caught a boat to China.

When the Chinese railroad ended, Gladys rode a mule for two days to Lawson’s town of Yangcheng, located in the interior where few missionaries had ever gone. Two weeks after Gladys arrived, Lawson died from a fall. Gladys wondered if she had made the right decision. All alone and with no money, she prayed for guidance. A week later, the regional governor knocked on her door. God had opened a door for Gladys to share the gospel in a most unusual way.

The governor provided his new foot inspector a small salary, a mule for transportation and four soldiers to protect her from hostile men. The cultural practice of foot-binding young girls’ feet had existed in China for 1000 years. Change did not come quickly. Women with tiny feet were considered beautiful. However, the custom caused many women to be crippled for life. The new law was sometimes met with resistance and violence in Yangcheng County.

Gladys traveled from village to village, educating citizens about the new law. Fathers who continued to bind their daughter’s feet would be sent to prison. Despite the hostilities, God granted Gladys divine protection, favor with the governor and local citizens, and opportunities to tell Bible stories. Not only did Gladys inspect feet, but she cared for the sick, visited prisons and became a mother to orphans.

Later, the governor helped Gladys start a school for the 94 orphans in her care, and he sent his children there. In 1936, she gave up her British passport and became a Chinese citizen. Her Chinese name became Ai-weh-deh. ‘The Virtuous Woman.’

Gladys Aylward was a missionary in China for more than four decades. When she died in 1970, she was honored by the Chinese government. Despite numerous challenges, she never wavered in her calling to China. Her story is an inspiring tale of an ordinary woman and an extraordinary God.

This was such an inspiring story–the name sounded familiar, but I do not remember having read all that before.

Very inspirational story. Thanks