1995 – Dallas, Texas: Carl Henry, a literacy recruiter, knocked on the door of the small, dilapidated house in south Dallas. He informed the older gentleman who answered the door that adult literacy classes were being offered a few blocks away at the old high school. George Dawson responded, “I don’t do nothing but sit around. I’m tired of fishing. It’s time to learn to read. Let me get my coat.”

George Dawson was born in 1898 in Marshall, Texas. He remembered his grandmother’s story of the day the plantation master called the slaves together and told them the confederacy lost the war, and they were free. George’s granddaddy bought 40 acres for $0.50 an acre. Over the years, the farm grew to 320 acres.

George started to work when he was 8-years-old. There was never time for school, so he never learned to read and write. He picked cotton, worked in a sawmill, built levees on the Mississippi River and worked for a railroad laying crossties. In 1938, he got a job with Oaks Farm Dairy in Dallas doing repairs to the machinery. He worked there for 25 years before retiring in 1963 at age 65. George did yard work for people in the community until age 90, then lived off his $520 a month social security check.

George kept it a secret his whole life that he couldn’t read. As a youth he quickly learned to recognize “Whites Only” signs and he was always embarrassed to sign his name with an X. He was ashamed that he wasn’t able to read menus or the newspaper. On several occasions at Oaks Farm, George was passed over for a promotion, because he could not fill out the paperwork.

George and his wife Elzenia had seven children. Every night George had his children show him their completed homework. None of them knew until much later that he could not read and write. Elzenia read the mail, paid the bills and balanced the checkbook while George worked menial jobs.

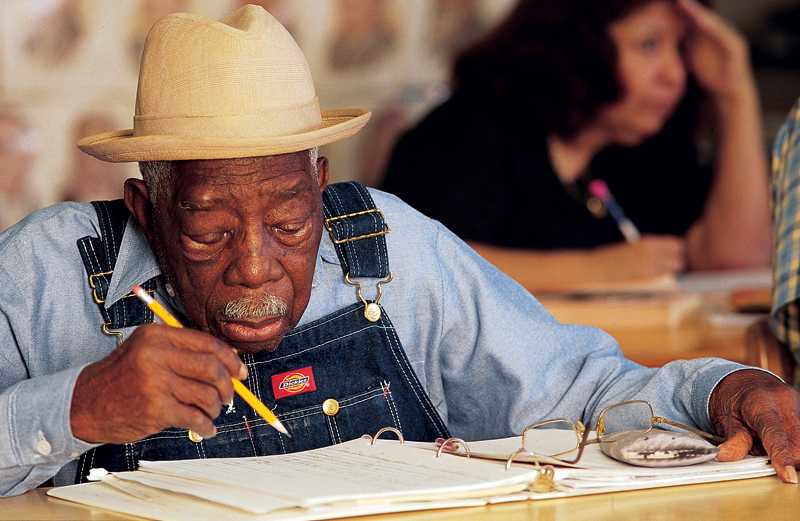

George had always dreamed of learning to read. In January 1996, at age 98, he finally got his chance. Carl Henry started from scratch, teaching George the alphabet. He learned it in two days. George insisted that they skip phonics. He was anxious to read words. Within a month George was reading a few simple sentences. Although Carl wanted to teach George to print, George insisted that he learn cursive writing so he could finally sign his name.

Elzenia died in 1985 and remarkably, at age 98, George still lived alone. He had all his hair and teeth, didn’t need a cane and rarely wore reading glasses. He had never spent a night in a hospital.

Every morning at 8 a.m. George sat on his porch with his lunch bag, waiting for Carl to take him to school. George never missed a day. He became an inspiration to his adult education classmates, who were mostly in their 20s and 30s. “If George can do it,” they said, “we can, too.”

On George’s 100th birthday, his adult education class gave him a surprise party. By then, George was reading on the third-grade level and for the first time in his life was able to read his birthday cards. And he was beginning to read his favorite book, the Bible.

In 2000, at age 102, George told his life story while Richard Glaubman, a teacher and writer from Seattle, captured it on paper. The book, Life is So Good, became a best seller. The book’s success enabled George to tear down his old house and build a new one. After traveling with Glaubman to promote the book, George returned to his routine of attending classes in English, science and math in the adult education program.

On July 5, 2001, George Dawson, age 103, died following a stroke. Today, not too far from his house is the new George Dawson Middle School. More than 600 students pass George’s statue each day and are reminded of his motto inscribed there, “It’s never too late.”

“You are never too old to set a new goal or dream a new dream.” Les Brown

This is such an inspirational story–an amazing person.