“He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.” George Washington Carver’s epitaph

1916 – Enterprise, Alabama: Anxiety was the order of the day in Enterprise, the county seat of Coffee County. The banks were reluctant to loan money to struggling cotton farmers and some farms had gone under. Newspapers predicted “the end of the Southern way of life.” The boll weevil was devastating the South’s economy and pushing farmers to the edge.

The boll weevil was a cotton farmers worst nightmare. In 1892, the tiny insect, a native of Mexico, first crossed the Rio Grande River into Texas and began eating its way eastward. The devastation would eventually stretch all the way to Virginia.

The boll weevils were first spotted in the Coffee County fields in 1915. The timing could not have been worse for the already struggling Alabama cotton farmers. After years of planting only cotton, their yield per acre was dropping because the plants had stripped nitrogen from the soil. Farmers were forced to plant additional acres. The rapid spread of the tiny beetles was frightening, destroying almost 60% of the county’s cotton crop.

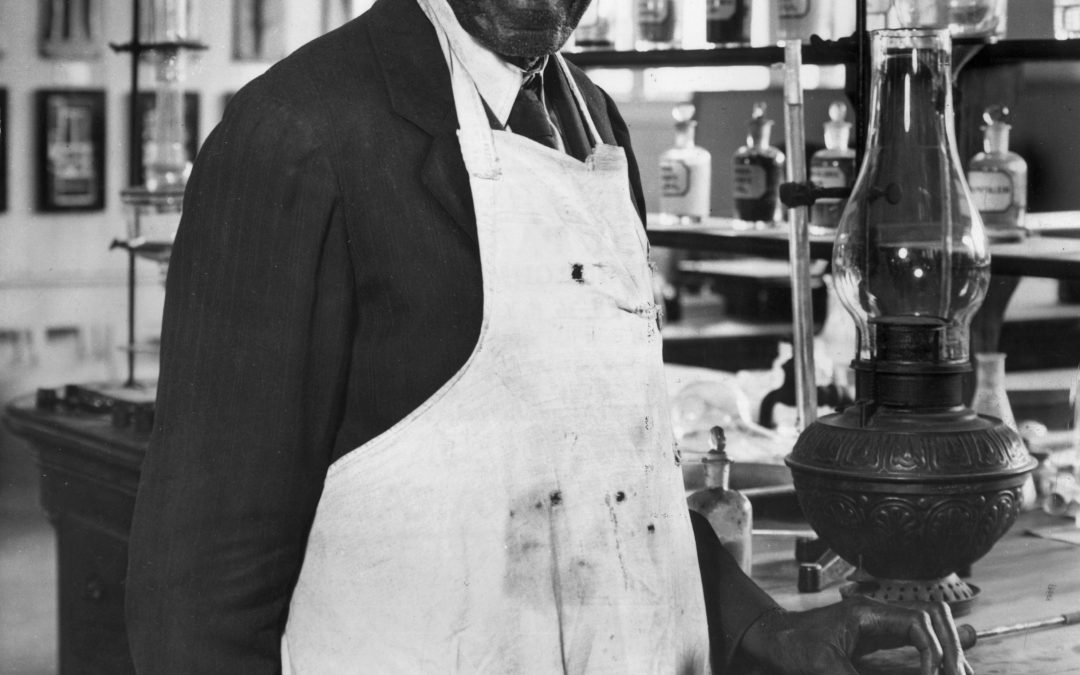

Just 90 miles away at the Tuskegee Institute, Dr. George Washington Carver, a former slave who was the South’s leading agriculture scientist and researcher, had been pushing for peanut-based crop rotation for a decade. Carver was the first African American student to enroll at Iowa State College of Agriculture, now Iowa State University.

In 1896, after earning a bachelor’s and master’s degree in botany, he joined the faculty at Tuskegee Institute. He seized the opportunity to help poor farmers in the South. He knew that Southern cotton farmers would one day suffer due to their over-reliance on this crop.

Carver recommended crop rotation or using fertilizers high in nitrogen content, but his suggestions fell on deaf ears. What did a “Peanut Man” know about raising cotton? A Black man from Iowa didn’t understand the situation in the South. Cotton had been the cash crop for more than 200 years, and it would always be king.

After the Coffee County cotton production dropped from 15,000 bales in 1915 to 5,000 a year later, farmers were finally ready to listen. Within a few months, Dr. Carver, county agricultural agents and a coalition of farmers had convened. After a lively debate, there was general agreement to follow Dr. Carver’s advice and scrap the 1916 cotton crop in exchange for peanuts.

Three years later, Enterprise and Coffee County were number one in the nation in peanut production, growing one million bushels of peanuts. Dr. Carver helped farmers turn a crisis into prosperity. He developed markets for peanut products, like oils and butters. Peanuts were also used as hog feed bringing prosperity to meat processing.

In 1920, the brilliant scientist exhibited 145 peanut products at the United Peanut Association of America conference. During his lifetime, Carver created 285 products from peanuts, including milk, shaving cream, soap, shampoo, and housing insulation from peanut shells.

Unlike many communities that no longer exist because of the havoc the boll weevil wrought on the south, more than 100 years later, Enterprise, Alabama is alive and well with a population of 26,000 people. The county’s main crop continues to be peanuts. Today the peanut fields are surrounded by manufacturing facilities and a military base.

At the intersection of College and Main Street there is a monument of lady in a white flowing robe holding an oversize bronze boll weevil over her head. In 1919, after a bumper peanut crop, grateful citizens erected a monument to the tiny cotton-eating beetle. The six-legged insect reminds a small town of the importance of resilience and flexibility.

Some have criticized a monument to a bug and no monument to Dr. Carver. He was invited to be the keynote speaker at the unveiling, but a storm washed out the railroad and he was unable to attend. Honored to help spur Coffee County’s economic revival, he supported the monument. Carver didn’t need fame and fortune; he found happiness in helping others.

Doctor Carver was a brilliant man. I love peanuts and peanut butter. I have seen the Bole Weevil Stature many times in Enterprise, Alabama. Use to drive thru there before they put in the bypass on my way to Brewton.