February 9, 1917, Sun Flower School – Elkhart, Kansas: Glenn Cunningham, age seven, and his 13-year-old brother, Floyd, walked the two miles to the one-room school. Floyd prepared to light a fire in the large pot-bellied stove, as he did most winter mornings, to warm the building. He loaded the wood into the stove and doused the logs with what he thought was kerosene – but the fuel container had been mistakenly filled with gasoline.

When he lit the match, the stove exploded engulfing both boys in flames. Floyd died several days later; Glenn survived but was burned on more than 50% of his body, mostly below the waist. The fire burned the flesh off his knees and shins, and the toes on his left foot were completely burned off. “Glenn might live, if he doesn’t get an infection,” the doctor advised, “But he’ll never walk again, he is too badly burned.”

When the doctor left, Glenn cried, “I will walk. I will walk.” His mother kissed his forehead and whispered, “I know you will. He is wrong.” Glenn got an infection a week later and the doctor recommended both his legs be amputated. His mother refused. She had lost one son and would not allow her other son to lose his legs.

Glenn survived the infection but his recovery was long and painful. Unable to straighten his legs due to the scar tissue, Glenn learned to stand by pulling up on the back of a chair. Each day his mother would push his wheelchair outside where he would practice pulling up on a fence and walking along the fence for hours. Ten months after the tragedy, on Christmas Eve 1917, he took his first unassisted steps. In time, Glenn discovered it was less painful to run than to walk.

At age 12, Glenn won his first racing medal at school. During his senior year of high school, he set the Kansas state record for the mile run at the state championship meet with a time of 4:28. A few months later in Chicago, Glenn broke the national high school record with a 4:24 mile, earning him the distinction of the greatest high school miler in history.

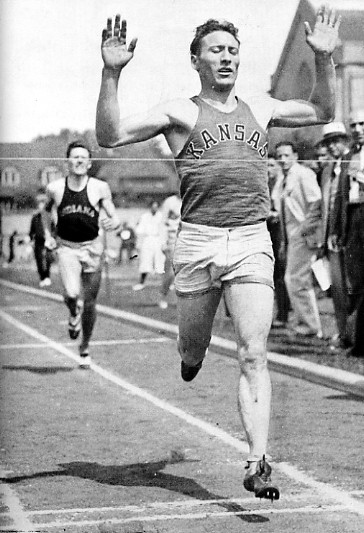

A decade after the doctor wanted to amputate his legs; Glenn signed a track scholarship with the University of Kansas. Dubbed the “Kansas Flyer,” he set numerous records during his college track days, including a world record mile of 4:06 minutes. In the 1936 Berlin Olympics, he broke the world record for the 1500-meter run, missing the gold by a fraction of a second, winning the Silver Medal for the USA.

Later in 1938, Glenn broke the world record for the indoor mile with a time of 4:04 and set his sights on winning the gold medal in the mile in the 1940 Olympics. When World War II caused the cancelation of the 1940 Olympics, he retired from the track.

After earning a bachelors and masters degree from Kansas, Glenn Cunningham received his Ph.D. in Physical Education from New York University in 1938. He was Director of Physical Education at Cornell College in Iowa for several years before he resigned, and with the help of his wife, started the Glenn Cunningham Youth Ranch in Kansas. The 900-acre ranch provided a home for orphans and children from troubled backgrounds. Through this program, the Cunningham’s helped raise more than 9,000 children during a 30-year period.

The seven-year-old boy, who was told he would never walk again, broke the world record for the mile or the 1500-meter run on seven different occasions. In 1974 the United States Track and Field Federation inducted Glenn Cunningham into its inaugural Hall of Fame class. In 1978, a decade after his death, Madison Square Garden in New York City recognized him as the most outstanding track athlete to perform in the building over the course of its first 100 years.

“When the race seems lost, when the odds appear unbeatable, when the pain is too much…never quit.” Glenn Cunningham

Pete, I just had a PTSD Flash that got my attention; my mother received a 2nd telegram, in April 1953, that I would not make it, from my wounds received in Korea! But, here I am, and I often wonder why I was spared, either to Serve, or Suffer, considering my Buddy was KIA at the time I was SWIA!

Yes, that three-mile walk got my attention, as it brought back the memories of walking barefoot, one-mile to catch the bus, to ride to Beatrice HS!

Great story!!

Great stories.