“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” Margaret Mead

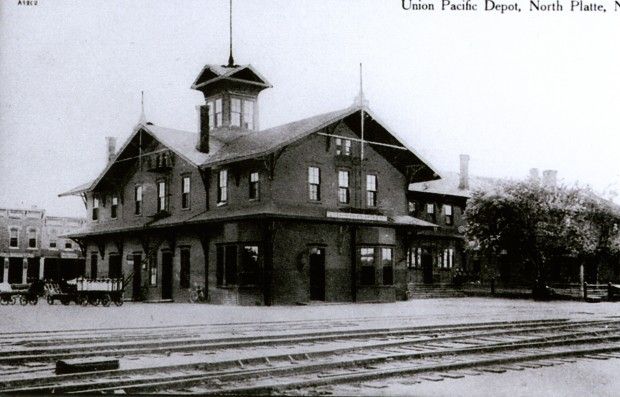

December 10, 1941 – North Platte, Nebraska: Rae Wilson, a 26-year-old store clerk, had an idea that volunteers could meet soldiers passing through North Platte on Union Pacific trains, offer them refreshments and thank them for their service. She wrote a letter to the local newspaper asking if they would convert the Union Pacific train depot into a canteen. She volunteered to coordinate the project. To her delight, Union Pacific and North Platte leaders supported her idea.

North Platte, a small town of 12,000 people, was located on the Union Pacific Railroad mainline. Passenger trains traveling coast-to-coast stopped at the depot for 15 minutes so that steam-driven locomotives could take on coal for their furnaces and water for their boilers.

The canteen began in earnest on Christmas night 1941, when five volunteers met the 11:00 p.m. train. Soon a regular schedule of volunteers was standing outside train windows with baskets of food, cigarettes, candy and big smiles on their faces. Soldiers were surprised by the reception they received and amazed to discover the refreshments were free.

Military protocol required soldiers to remain on the train at stops, but as word spread about the North Platte reception, military regulations were relaxed. When the train stopped, many soldiers ran to the canteen. There they discovered friendly volunteers and a smorgasbord of food.

A typical spread consisted of fried chicken, egg salad or tuna salad sandwiches, fresh fruit, cookies, cakes, milk, and hot coffee. Volunteers brought their newspapers and magazines to share with the troops. During a time of national rationing of food, the people of North Platte sometimes did without to provide refreshments for the soldiers.

The train arrival time was confidential, but Wilson worked out a notification system with Union Pacific. The message, “The coffee pot is on,” informed the canteen that a train was headed their way. The troop trains rolled through North Platte between 5:00 am and 11:00 pm. During the peak times, 20 to 25 trains a day stopped at the depot. The bigger trains sometimes carried 3,000 to 5,000 soldiers.

The number of soldiers was more than the local volunteers could handle, but word quickly spread to other communities. Church groups and civic organizations began showing up to volunteer. A ladies group from Shelton, Nebraska, a small town 120 miles away, rode the train to North Platte one day each week bringing angel food cakes and cookies.

In all, 125 communities in Nebraska and eastern Colorado participated in the project. With many of the men on military duty, the volunteers were mostly women, many of whom had sons fighting in Europe and the South Pacific. Although they could not help their sons, they could treat the soldiers as their sons. To the women, the boys weren’t just soldiers; they were “Our boys, the hope of America.”

Many of the young soldiers were lonesome and scared, wondering if they would ever see home again. The quick stop in North Platte was like being back home. It reminded them that what they were doing mattered and was appreciated.

The volunteers had no idea how long World War II would last or how long the project would go on. The war ended on Wednesday, August 15, 1945, but the canteen stayed open another eight months until most of the troops were home. It closed on April 1, 1946.

From Christmas night 1941 until April 1946, volunteers never once missed greeting a train, day or night. Rae Wilson’s idea and the support of thousands of volunteers touched the lives of more than six million soldiers who stopped at the North Platte depot-turned canteen. Sixty years after World War II ended the mayor of North Platte was still receiving thank you notes from old soldiers who never forgot their experience there.

This was so wonderful that these people did this & certainly meant so much to the soldiers.

Wonderful story. Thank you Pete.