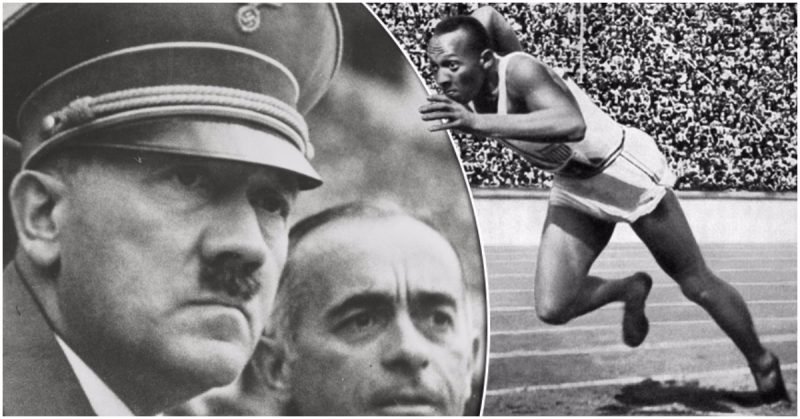

August 1936 – Berlin, Germany: German Chancellor Adolf Hitler was excited to host the Summer Olympics. It allowed him an opportunity to showcase Nazi Germany on the world stage. He had high hopes that German athletes would dominate the games and validate his philosophy of Aryan supremacy. However, a 22-year-old dark-skinned sprinter from Oakville, Alabama, would steal the chancellor’s show.

James Cleveland “J.C.” Owens was born in September 1913, in Lawrence County, Alabama. His father scratched out an existence by sharecropping 40 acres of land. By age 8, J.C. could pick 100 pounds of cotton in a day.

At dinner one night, J.C. announced he wanted to go to college. His father told him, “Son, get that crazy idea out of your head.” But his mother smiled, “Maybe someday J.C. if you work hard.” Although sickly, frequently suffering from colds and pneumonia, J.C. was his mother’s special-born son. She affectionately called him her gift child.

In early 1923, hoping for a better life, the Owens joined other African American families and took the train north. They settled in a small apartment in Cleveland, Ohio. The children were excited to have running water and electric lights for the first time.

In the third grade, when the teacher asked the nine-year-old his name, she thought he said “Jesse,” and J.C. would be Jessie Owens for the rest of his life. In junior high school the track coach, got him interested in running. At East Technical High School in Cleveland, Jesse tied the world record for 100 yards and set national high school records for the 100 and 200-yard dash and the long jump.

Ohio State University recruited Jesse Owens to run track, not by offering him a scholarship, but by finding his father a job. It was a difficult period for Jesse. Because of his skin color he wasn’t allowed to live in student housing but had to live off-campus. When the team traveled, Jesse ate his meals on the bus or in a different restaurant. He also stayed in separate hotels than his white teammates.

Despite the hardships, Jesse excelled on the track. In May 1935, at the Big Ten track championship, the “Buckeye Bullet” set three world records. His records included a 9.4 second 100-yard dash, a 20.2 second 220-yard dash, and a 26’ 8” long jump, a mark that would stand for 25 years.

The Olympic games began on August 1, 1936. Four days later, when Jesse Owens won the 100-meter gold medal with a time of 10.3 seconds, Adolf Hitler left the stadium. The next day Jesse scratched on his first two attempts in the long jump round. Before his third try, a stunned stadium watched as Jesse’s biggest foe, German long jumper Luz Long, placed his towel one foot from the takeoff mark to help Jesse know where to start his jump. Aided by this kindness, Owens jumped 26’5” to win his second gold medal. Long was the first to congratulate him.

On August 5, Jesse won his third gold medal with a time of 20.7 seconds in the 200 meters. Then on August 9 he ran the lead leg of the men’s 4 x 100 meter relay as the U.S. team captured the gold medal in 39.8 seconds – a world record that stood for 20 years.

Jesse Owens became the first American to win four Olympic gold medals in track and field. The German Chancellor refused to meet him or shake his hand on the medal stand. It did not matter. The fastest man in the world, and darling of the 1936 Olympics, had his four gold medals and the hearts of the world.

In 1996, Oakville, Alabama, dedicated the Jesse Owens Museum and Park as the Olympic Torch came through the community, 60 years after Jesse Owens stole Adolf Hitler’s Olympics. Today the dormitory in Berlin where Jesse Owens lived during the Olympics is a museum commemorating his accomplishments at the games.

“The battles that count aren’t the ones for gold medals. The struggles within yourself – the invisible, inevitable battles inside all of us – that’s where it’s at.” Jesse Owens