May 13, 1862 – Charleston, South Carolina: Robert had planned his escape for weeks. On this foggy night,Charles Relyea, captain of the C.S.S. Planter, and his two white crewmembers left the ship after dark to spend the night ashore with their families. Smalls had waited for this opportunity to steal the ship and sail to freedom. It was now or never.

Robert Smalls was born in 1839, in Beaufort, South Carolina, in the small slave quarters behind owner John McKee’s house. His mother was the McKee’s house servant. Robert never knew his father, although rumors suggested it was McKee or his son Henry. As a teenager, Robert began working on the Planter, a vessel designed to move cotton around the harbor. At 19, he met Hannah, a slave working at a Charleston hotel. Not long after they met, he obtained permission from both their owners to marry her.

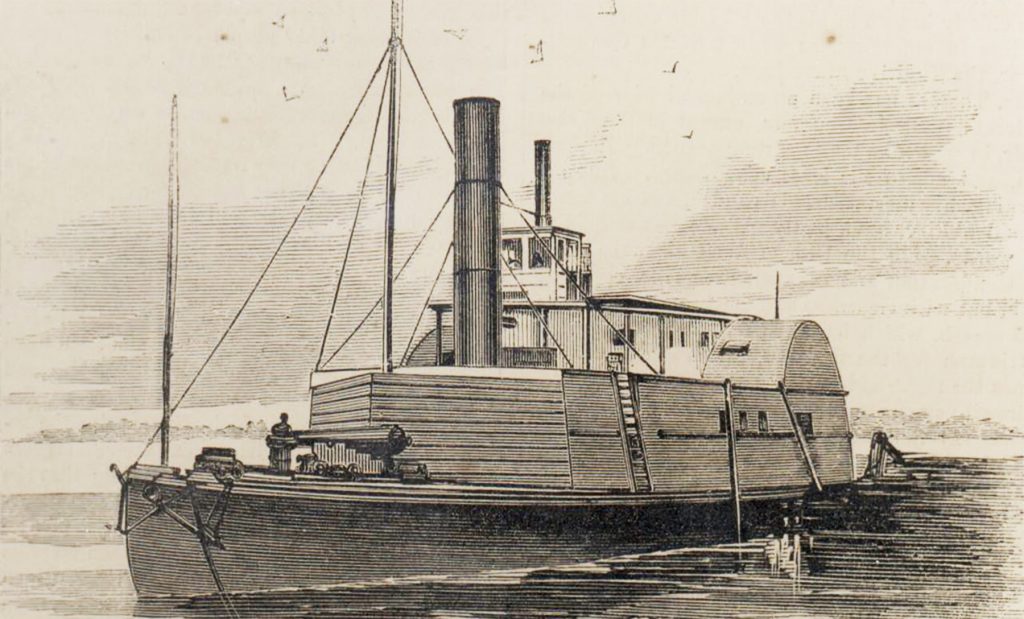

When the Civil War started, Confederate forces seized the Planter, a steam-driven paddle wheeler, and converted it into an armed transport vessel. Robert, who had been navigating the vessel around the harbor for several years, served as the Planter’s pilot but was called the boat’s wheelman, because only whites could hold the pilot rank. Six other slaves rounded out the 10-man crew.

Fearful that he might be separated from Hannah and his two children during the war, Robert shared a daring and dangerous plan with her. “What will happen if you are caught?” Hannah asked. “I will be shot,” Robert responded. “Then I will die with you,” Hannah whispered. They were willing to risk it all for their freedom.

Captain Relyea occasionally left the ship to be with his family at night, trusting Robert and the other slaves to stay on board and watch the vessel. On May 13, when the captain went ashore, 22-year-old Robert waited until 2:00 a.m. to begin his escape. He put on the captain’s jacket and straw hat in hopes of disguising himself and got the ship underway.

They picked up Hannah and the two children, as well seven family members of the crew, at the West Atlantic wharf nearby. Robert then slowly maneuvered the ship out of the harbor. If captured, he planned to blow up the ship and go down in flames.

At 4:15 a.m., Robert sounded the boat’s horn, two long blows and a short one, a signal he knew well, at two Confederate checkpoints, Ft. Johnson and Ft. Sumter – where the Civil War had begun 13 months earlier. Once clear of the forts, Robert steered the ship toward the Union blockade 10 miles off the coast.

At daylight, the crew lowered the Confederate flag and hoisted a white bed sheet as a sign of surrender. As they approached the Union ship, U.S.S. Onward, the bizarre sight resulted in Onward Captain John Nichols opening the gun port and preparing to fire. Just before he fired, a sailor yelled, “I see a white flag,” and the ship was spared. Robert boarded the ship with, “Good morning, sir. I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns.”

Robert Smalls had courageously commandeered a heavily armed Confederate ship and delivered the ship’s armament and its 17 Black passengers to the Union. He was a hero in the North and his courage earned him a seat at the table with abolitionist Frederick Douglas. Together they were able to influence President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to allow Blacks to enlist in the war effort.

In October 1862, Robert returned to Planter as its pilot. His ship was part of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. He became a Union naval hero participating in 17 naval engagements, including an attack on Ft. Sumter in 1863.

After the war, Robert served in the South Carolina state assembly and senate, where he helped found the Republic party in the Palmetto state. Later, he served five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1874 to 1886. Robert Smalls died in Beaufort, South Carolina, in February 1915, in the McKee house, which he owned.

“Freedom means the opportunity to be what we never thought we would be.” Daniel Boorstin

Love the story. Thanks

Good story. I live just north of Charleston now working for Ingevity.

Thanks for being so faithful to publish good stories like this one.