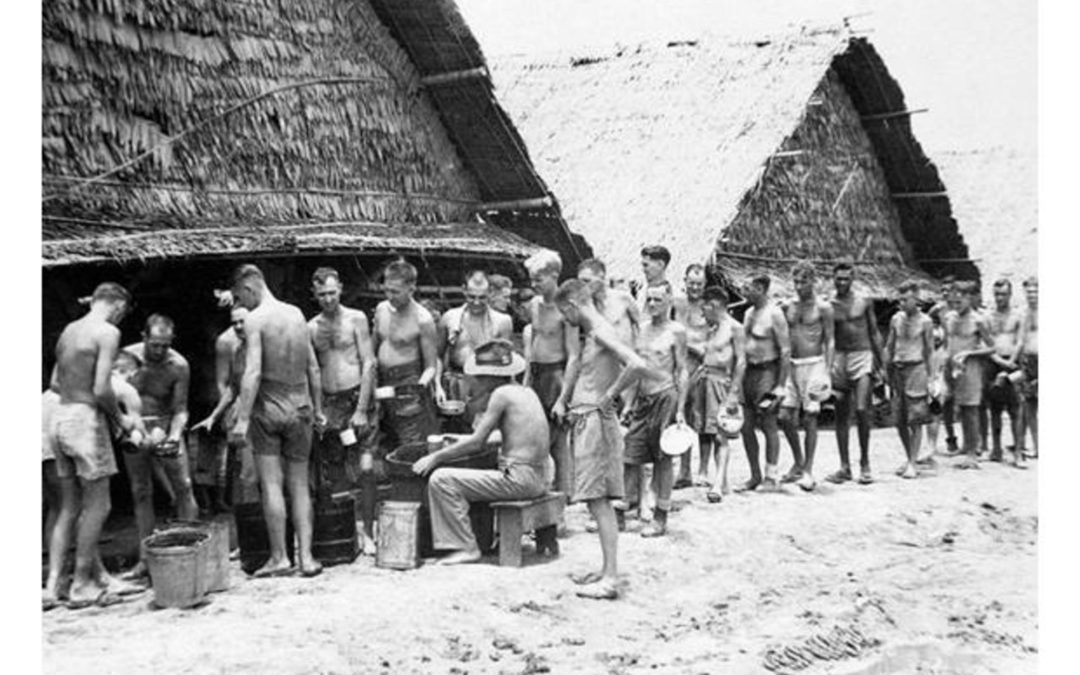

In the spring of 1943, Scottish Commander Ernest Gordon lay dying in the infamous Japanese prison camp, Chungkai, located in a Thailand jungle on the bank of the Kwai River. He had been placed on the muddy ground next to several corpses in the filthy camp hospital/morgue, known by POW’s as the “Death House.” He penned a final letter to his parents telling them he loved them and cursing God and the Japanese. Then he waited for death, welcoming it as an escape from the hell he had experienced since being captured in February 1942.

On May 31, two buddies from his 93rd Scottish Highlander Unit brought their Captain a rice ball trimmed with a banana in celebration of his 27th birthday. They were shocked by Gordon’s appearance. The next day the buddies, Dusty Miller, a Methodist, and Dinty Moore, a Catholic, arranged to get Gordon out of the hospital and carried him to a makeshift bamboo hut they had built. At night, after being forced to work from sunrise until dark on the notorious Burma/Thailand Railroad, the two Christian POW’s shared their meager rations with Gordon. Miller patiently cleaned the infected boils on Gordon’s bony legs and back and picked the lice from his body.

After watching hundreds die from starvation, torture, and disease, Gordon had accepted his fate and wanted to be left alone to die. He struggled to understand why two men, who were starving, would willingly share their rations with a dying man. Despite Gordon’s bitterness toward them, Miller and Moore came each night with food and pages from a tattered Bible. Another POW gave a guard his watch in exchange for medicine for Gordon. Slowly, Gordon realized the men had found the answer he needed. Their love freed him from a prison of hatred, hopelessness, and despair, and gave him new faith and a desire to live and not die.

In the Chungkai POW camp, there was no church, no chaplain, and no religious services. Because of his leadership position and college degree, once Gordon’s condition improved, he was asked to lead a Bible study on the edge of the camp. What began with a single verse, and his story shared with a dozen POW’s, grew to influence hundreds of men. Men stopped stealing and fighting over rations, and began sharing their food. Hatred of the Japanese guards was replaced with forgiveness.

After the war, Gordon underwent several months of medical treatment to regain his health. He became a minister earning degrees at the University of London and Hartford Theological Seminary in Connecticut. In 1950, he was ordained by the Church of Scotland and came to Long Island, New York, to pastor churches in Amagansett and Montauk. In 1954, Gordon became the Presbyterian chaplain at Princeton University, and later dean of the chapel. He served at Princeton 26 years until his retirement in 1981.

After his retirement, Gordon moved to Washington, D.C. to be president of Christian Rescue Effort for the Emancipation of Dissidents, an organization that helped free prisoners from eastern European countries. He chronicled his three-year POW experience in the powerful memoir Through the Valley of the Kwai, which later inspired the 2002 movie To End All Wars.

An estimated 60,000 allied POW’s plus 240,000 Asians workers were forced to build the 200-mile railroad from Thailand to Burma, a five-year project, which was completed in 12 months. Approximately 13,000 POW’s and 80,000 civilians died from the brutal conditions and were buried along the railroad. Dinty Moore died when his small boat was torpedoed on the way back to Japan at the end of the war and Dusty Miller escaped from Chungkai but was later crucified by the Japanese. Ernest Gordon died February 16, 2002, at the age of 85.

“Faith could not save us from the miserable prison camp, but it could take us through it.” Ernest Gordon