“Success is to be measured not so much by the position one has reached in life as by the obstacles he has overcome while trying to succeed.” Booker T. Washington

July 1987 – Kingston, Jamaica: Devon Harris saw the flyer on the bulletin board. “Dangerous and rigorous trials to choose the nation’s first Olympic bobsled team.” He thought it was a joke. Jamaica entering a bobsled in the winter Olympics in Calgary, Canada? Ridiculous. He told fellow Army buddy Dudley Stokes, “Hey, mon, no one could ever get me to go on one of those things. They are fast and dangerous.” They both laughed.

A week later, Harris and Stokes were summoned to the colonel’s office. The Olympic committee was having trouble finding bobsledders. Jamaica Olympic track team members weren’t interested in being bobsledders because they were training for the 1988 summer Olympics in Seoul, Korea. The colonel ordered them to try out.

In the spring of 1987, George Finch, a former attaché at the American Embassy in Kingston, watched the annual pushcart derby. The pushcarts racing through the streets of Kingston reminded him of bobsleds. Finch reasoned that Jamaica’s world-class sprinters should be great at pushing a bobsled. The idea of a tropical island nation competing in a winter sport was beyond absurd, but Finch’s idea got legs.

He called the Jamaica Olympic Association. They laughed before realizing that Finch was serious. Then they agreed to support a team after Finch committed to completely fund the project. He hired a former American bobsledder to coach the team. With the 1988 Calgary Olympics just eight months away, time was critical.

At the trials in July, Harris, a 23-year-old Army captain and one of Jamaica’s top middle-distance runners, and Dudley, a 25-year-old Army helicopter pilot, were chosen for the team. Two other soldiers who were top national runners also made the team. The practice began a few weeks later. In the afternoons after work, the team pushed a cart on a grass field on the army base.

In September, the Jamaica team saw a bobsled for the first time at the World Games in Austria. The Austrian team loaned them a sled and taught them how to push and steer it. They were scared to death on their first run on a bobsled at 85 miles per hour. But against all odds, Jamaica surprised the bobsledding world by meeting the qualifying time for Calgary.

In November, still without a sled, the team left balmy Jamaica and headed to Calgary to train. They sold T-shirts to raise money and purchased a used sled from the Canadian team. A week before the Olympics began, team member Caswell Allen fell on the ice and injured his shoulder. Stokes’ brother Chris, a sprinter at the University of Idaho, who was there to cheer for his brother, was drafted as the fourth team member. They taught him what little they knew about their new sport in a couple days.

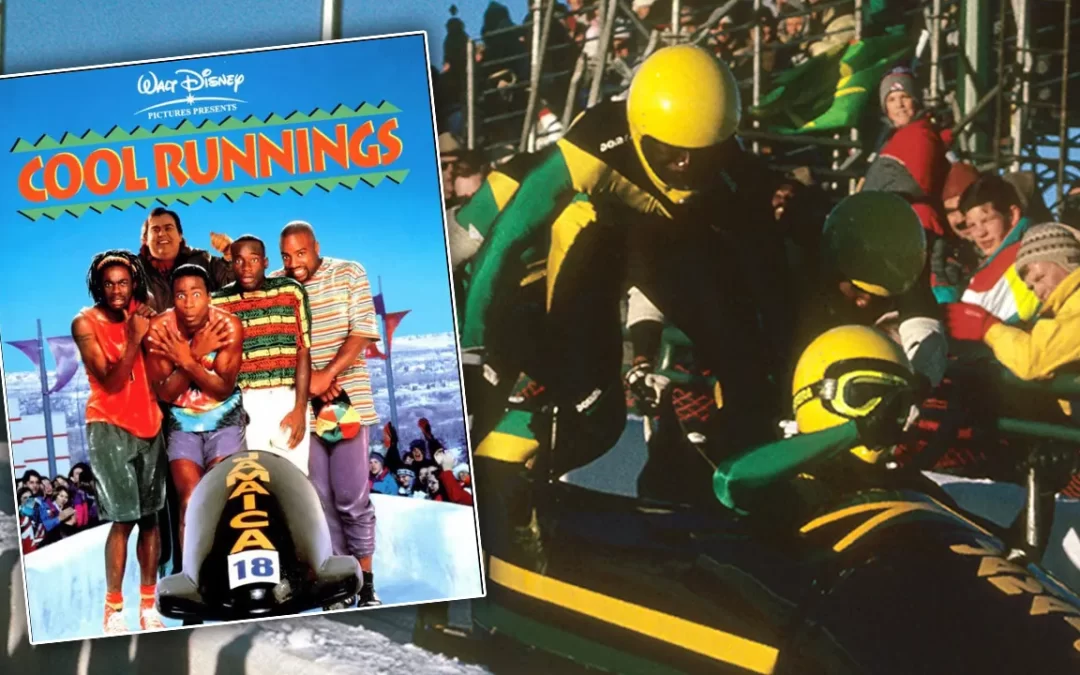

As the news spread about the Jamaica bobsledders, they became one of the popular stories in the winter Olympics. Everybody loved the underdog green and gold team. Whenever team members left the Olympic Village, they were mobbed by fans.

On February 20, the first day of the bobsled competition, Jamaica had trouble getting in their sled after the push and finished dead last. But on day two, they got off to a fast start and recorded the 7th fastest time at the 1988 Olympics.

On their third run, the sled got too high on the wall at turn nine and crashed. There were no injuries, except for the team’s pride. With the world watching, the embarrassed team members pushed their sled 100 meters to the finish line. Their Olympics were over, but their story was only beginning. The Jamaica bobsled team became a worldwide sensation because they dared to try – despite the odds, the circumstances and the laughter.

According to Harris, “We felt like we let Jamaica down. If we hadn’t crashed, there probably would be no Jamaica bobsled team today. The crash fueled our desire to come back.” Today, 35 years after Calgary, Devon Harris and Dudley Stokes are still involved with Jamaica’s Olympic bobsled program. “Mon, we haven’t won a medal, so we keep on pushing,” Harris says.

Great story.